“The first thing people do is stroke the walls – it’s tactile, there’s something about it that makes people want to touch it.” Alex Gibbons

On April 28th 2017 the first clay dabbins building to be constructed on the Solway Plain for more than a century was officially opened.

It has been an interesting story, driven along by the boundless enthusiasm of Peter Messenger, Chris Spencer and earth-buildings specialist, Alex Gibbons.

***

Last July, Clayfest 2016 – a week-long celebration of traditional building techniques, organised by Earth Buildings UK and Ireland (EBUKI), Solway Wetlands Landscape Partnership, and the RSPB – was taking place at the RSPB’s Campfield Reserve. Tents and campervans formed a small encampment behind one of the barns for, despite Clayfest being held at Bowness, on a corner of the Upper Solway coast, people had come from as far away as the USA and the Netherlands to take part.

There were talks, and tours, and workshops on the ‘rammed earth’ technique of building, and on techniques for making and using earth plasters. Chris Spencer, Manager of the Solway Wetlands Landscape Partnership, was running the clay dabbins workshop, using the traditional method of layering straw and wet clay to build a bird hide overlooking the pond.

I had dropped in briefly half-way through the festival, on the hottest day of the year. It was lunchtime and everyone was sitting in the shade, chatting and eating healthy-looking mixtures of vegetables and fruits but Chris immediately broke off from his more substantial lunch to give a quick tour.

In one of the barns a mound of reddish local clay was ready to be mixed into plaster; more clay was down by the developing bird-hide. “Three hundred tonnes,” Chris said. “It was dug up from near one of the ponds just along the track.”

In the ‘rammed earth’ area, plywood was being cut and screwed together to make the large arch-shaped ‘form’, into which clay would be pounded.

Further along, what looked like sandcastles were lined up in front of a straw-bale wall; books and a whiteboard suggested theory rather than practice had been occupying the time. “They do a lot of talking,” Chris explained with a grin.

Down by the pond, Chris’ group had not only been talking but had been working hard. The hide was progressing fast, the first layers of dabbins already in place on top of a low drystone wall of red sandstone blocks.

Next to it, the early stages of the Clay Dabbins House – which would eventually be an exhibition area to explain the Solway’s clay dabbin heritage – were baking gently in the sun, the layers of straw and stamped wet clay now hardened and firm, the walls awaiting a roof and inner and outer lime-plaster coatings.

In one of the Reserve’s other barns, an intriguing array of jars and earth materials were being laid out for a Clayfest demonstration, but more eye-catching was the future roof of the clay dabbins building. Here were baulks of oak which had been cut and chiselled into traditional curves; holes drilled, offset, ready to receive the wooden pegs that will hold the pieces together – a functional structure, yet sculptural and majestic.

What and where are the clay dabbins buildings?

Before we tell the story of Campfield’s little clay dabbins house, let’s look at clay dabbins buildings in general, a type of vernacular architecture found previously on both sides of the Upper Solway, but now mainly – and in decreasing numbers – on the Cumbrian side.

In a landscape formed on glacial till, gravel and mud, with very little ‘country rock’, how do you build a dwelling? You use the materials to hand – the earth and clay, and straw, and whatever trees you can fell for timbers. You need some stone too for a plinth, the foundation of the walls, lest rising-damp gradually liquefy the clay construction; perhaps the ruins of Holme Cultram Abbey or the Roman wall can provide a source, otherwise cobbles or field-stones must do. And if your friends and neighbours will help you tread and mix the clay with straw, then the walls will rise quite quickly.

‘It is conceivable that it could be done in a day, using lots of people from the village, say. People with the fitness of the 18th century, rather than someone like me who stops for an egg sandwich!’ Alex Gibbons.

The advantage of the dabbins method is that it is quick. Peter Messenger is a local expert on the Solway’s dabbins buildings, and has written a delightful and well-illustrated article with practical instructions about their repair.

A “serviceable mixture [of earth for the walls] could contain 30% (by weight) of stone/gravel (from 5mm to 40mm); 30% of coarse and fine sand; 15% silt and 25% clay. There are examples on the Solway Plain where the proportion of silt and clay in total can be as high as 80% and these walls are as hard and compact as others which have 50% of stone and gravel. So there are no hard and fast rules.”

By adding straw, the whole becomes, essentially, a ‘composite material’ – the straw lends strength and prevents cracking. The amount of water added to the mix is critical (neither too much nor too little, cf Goldilocks).

“The ratio of straw to mud is when it looks about right! You get in as much straw as possible, it adds tensile strength.Sand helps with the plasticity, so it’s not too claggy.” Chris Spencer

Then the well-trodden mix is lifted onto the wetted plinth, and spread and trodden again.

Peter Messenger writes that

“The layer should protrude a little beyond the line of the plinth (c. 50mm) and once a depth of c.100mm has been reached a thin layer of loose straw is spread over the surface of the lift. This will appear to be about 50mm deep but once the next layer has been laid on top of the straw its depth will reduce to about 15mm or less.”

These interleaved layers of straw act to suck out the moisture from the mixture, and because all the layers are thin the wall can be built to its full height without having to allow intermittent periods for drying-out.

During construction, lintels for doors and windows are put in place, and traditionally the supports for the roof were wooden ‘crucks’, tied together by wooden cross-trees, often with purlins running the length of the roof.

Various materials – including turf and heather – were used for thatch, and the walls were rendered inside and out with lime-render, to prevent rain penetrating the dabbins and causing it to slump.

A few years ago, I joined one of Peter Messenger’s walking tours around Burgh-by-Sands, where several dabbins buildings (variously decaying or restored) and cruck barns remain. He showed us a typical ‘long-house’, the living end of which was separated from the byre by a cross-passage; on another house, the cement-rendering had come away to show the layered dabbins underneath. A handsome cruck barn behind a farmhouse had been recently patched with new dabbins.

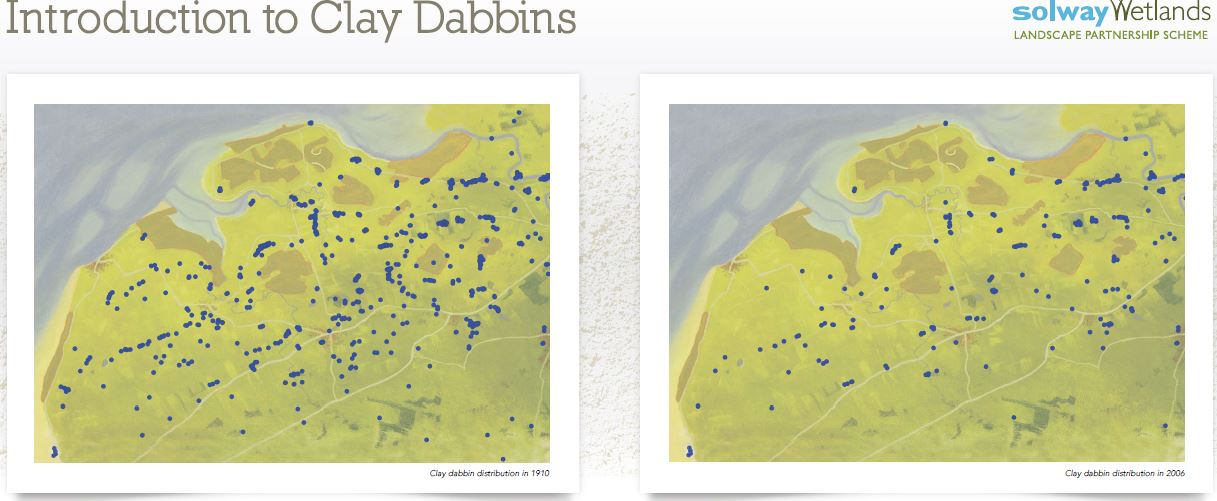

An early 1900s survey found about 1500 dabbins buildings around the Solway Plain, but by the time Nina Jennings carried out her own survey nearly twenty years ago there were only about 300 remaining. Her 2003 book, Clay Dabbins: Vernacular Buildings of the Solway Plain is the classic reference book, containing entertaining stories of some of the home-owners – and Jennings herself was an extraordinary woman, who started a degree in electronic engineering, was a member of the anti-war Committee of 100, active in CND, and a keen walker and skier; she died in 2015.

Peter Messenger’s own surveys have found many dabbin buildings in a sorry state of disrepair, with damaged rendering and unstable walls. The problems are caused by water ingress – “Waterlogged clay turns to mud, which slumps and collapses.”

He was instrumental in persuading Alex Gibbons, a William Morris Craft Fellow specialising in earth buildings, to move to Cumbria and become practised in restoring dabbins buildings. (An update on Alex’s work is in my ‘Quicklime’ post, as part of the ‘Limestone’ series.)

They, and Chris Spencer of the Solway Wetlands Landscape Partnership (SWLP), realised that to help people – owners surveyors, builders – understand how to protect and repair this special type of building on the Solway Plain, a practical demonstration would be not only useful but an entertaining (and muddy) project that could gather local volunteers – of all ages – to its heart.

And so, on April 25th 2016, the dabbin building was started, with financial and other support from a large number of organisations: it was part of a four-year grant to the SWLP from the Heritage Lottery Fund, and has been constructed on the RSPB’s Reserve at Campfield near Bowness-on-Solway.

Building the Clay Dabbin House

It’s been a wildly popular project. Hundreds of volunteers have helped, including a group of land-agents and RSPB wardens, fit retirees and conservation volunteers of all ages. “A group of building inspectors came out to do several training days – before that they had no idea about dabbins buildings,” Alex said. Chris worked especially with groups of school-children: more than 150 students came from seven local schools. “Local kids came from villages where there were clay dabbins buildings. They used their hands – hand-balling the mixture – and then forks. It was a great opportunity for them and we loved having them around. It helped that it was fantastic weather!”

The plinth of Penrith sandstone was laid, marking the base of the 4 metre by 5.5 metre building. “There’s no damp-proof course,” Alex explains. “The stones have gaps between them. As long as you use breathable materials, any water should evaporate. It’s all about being able to get the water away again.”

Mixing the clay and sand and straw is heavy work. “We used a tractor to do a batch-mix. It lifted the clay really, really high then dropped it, a big splodge,” Chris laughed. “We built it in four-inch lifts, then put a layer of straw on top. Then you immediately build the next layer on top of the straw, which binds it all together. As we got higher we put up staging, so we could raise the floor level and then just tipped the material onto it. This stuff is incredibly, incredibly heavy – so we used a tractor bucket to lift it.” The sides of each layer are sliced off flat where they slump over the layer below.

Constructing the building with the help of volunteers inevitably took longer, because it depended on availability of volunteers, of Chris and Alex – and, of course, on dry weather. As Alex said, “If I’d been building it with a team of guys that I’d trained, I reckon we could do the clay walls in three weeks – obviously with the help of a tractor, too. It is conceivable that it could be done in a day, using lots of people from the village, say. People with the fitness of the 18th century, rather than someone like me who stops for an egg sandwich!”

By May 2016 the dabbins layers beneath the window were in place; by July the wooden window-frame had been incorporated and the timbers for the roof had been prepared (see photos above).

Some of the oak – for the wall plates, the ridge beam, rafters and so on – was sourced locally, from wind-felled trees at Setmurthy.

“We went for truss construction in the end, not cruck,” Chris explained. “Mick Read, the joiner, is a genius with oak!”

Mick, who lives across the border in Canonbie, told me that he started as an engineering apprentice, then went into carpentry making furniture, and his interest in wood led him to tree surgery, “specialising in portable chain-saw milling. It’s small-scale equipment, quite light to transport – but time-consuming and slow. Basically, I have the option of going into a woodland, selecting a tree, and then milling the wood that has a bend in it.” In other words, producing timber that has two flat sides and two curved sides.

He found the oak for the truss – the tie beam, king post, truss members and wind braces – “at the back of the Canonbie sawmill. There was a ‘firewood pile’ of oak trees. The owner said ‘Take anything you like’. He let me chainsaw it and take it away, and gave it to the dabbin for free! I milled it at my house, framed it, then dismantled and labelled it, and brought it here.”

Mick also made the wedge-shaped pegs, and drilled the off-set holes in the beams. ‘You hit the pegs in, and the wood shrinks and tightens up the pegs. It’s quite an old way of construction.’

In August, he supervised the lifting and fixing of the truss roof timbers. As project photographer Fiona Smith and I watched, Chris and volunteers had little trouble steering the timbers into place. Chris was full of admiration: the tractor-driver “just dropped it onto the tenon on the kingpost and it fit so well we just had to give it a knock with a hammer.”

We hastily found a sprig of hawthorn and Fiona climbed up to nail it in place for the ‘topping-out’ ceremony.

Wilson Irving got a small bursary from SWLP to take part in the EBUKI 2016 festival, and has worked on the dabbins house throughout. “I came on training days, and to the workshops on making dabbin and heather thatching. I was involved more or less from the beginning. I didn’t do the drystone wall at the bottom,, but I helped with the dabbin, put on the wooden wall plates – they rest on the dabbin and spread the load of the roof. And two of us helped Alex build the gables. I enjoyed it all – but seeing the truss go up was the best bit.”

That was Chris’ favourite moment too. “It was all good! But lifting the roof timbers on was very good, it felt like it was marking a sense of completion, the mud work was over.”

Over the next couple of months, the rafters were nailed in place and the thatcher William Tegetmeir from Scarborough, “a real craftsperson” according to Chris, laid the heather thatch. The door and window were completed and the building was water-tight – but not yet weather-proof.

The rendering of the inside and outside walls

was done by Alex early this year. “The outside was done by harling – using a scoop-shaped trowel and throwing it on. I used a limewash of pure lime putty mixed with pure clay putty – the clay is screened down and water added.” In contrast, the inside walls are smooth, with flat plaster that reflects the light.”

Then there was the floor. “The base layer [of the floor] is about four inches thick, it’s rubbish, screed – everything that didn’t go through the screen. The top layer’s screened-down mud mixed with the sand and tamped down.”

John helped with the tamping, and we went to help again on the day the ox-blood was to be added.

As we arrived, two dumpy bags of Dalston sand were being delivered to the dabbins’ door. “You’d think we could go and get some sand from the Solway just up the road,” Alex said, “but it’s all too muddy.This sand’s slightly rough, it holds together well.” He squeezed some to show us, and it kept its shape.

And the ox-blood?

“I heard about blood from various people – it’s one of those folklore things.”

We were using dried and powdered blood. We tried mixing the powder with water to various consistencies, and there was much hilarity and discussion about the best way to apply it to the surface of the floor.

“I’m calling it experimental archaeology,” Alex said. “It sounds better than saying I don’t know what I’m doing! When I’ve looked at old floors, they’re always really black.”

In the end, Alex painted on the mixture. Apparently it was very smelly and ‘furry’ a week later! But on the day of the official opening, April 28th 2017, it was clean and firm, although it was generally agreed it would probably need a linseed coating to ‘fix’ it.

***

Three pupils from Kirkbride Primary performed the official ribbon-holding and cutting, and the building – now fitted with solar-powered LED lights and very helpful interpretation boards – was open, a year after it had been started.

As Chris Spencer said in his opening speech, “Many hundreds of people have helped – with the drystone walling, the clay-building, the thatching – it’s been quite an amazing year centred around the building.”

The dabbins house “shows how the Solway vernacular buildings were made. It’s also important to show that they are under threat around the Solway Plain. We hope from this to help people understand how to care for them and mend them.”

And then, of course, there was Elizabeth’s cake…